by Mark Staples and Danya Rumore

Mark and Danya here. During the INC5 negotiations, we’re covering issues related to mercury waste, supply and trade, and artisanal and small scale-gold mining (ASGM). Here, in our second installment, we provide an overview of mercury supply and trade, discuss what is already included in the draft treaty text about this issue, and explain what is now being discussed and will hopefully be decided in the days ahead.

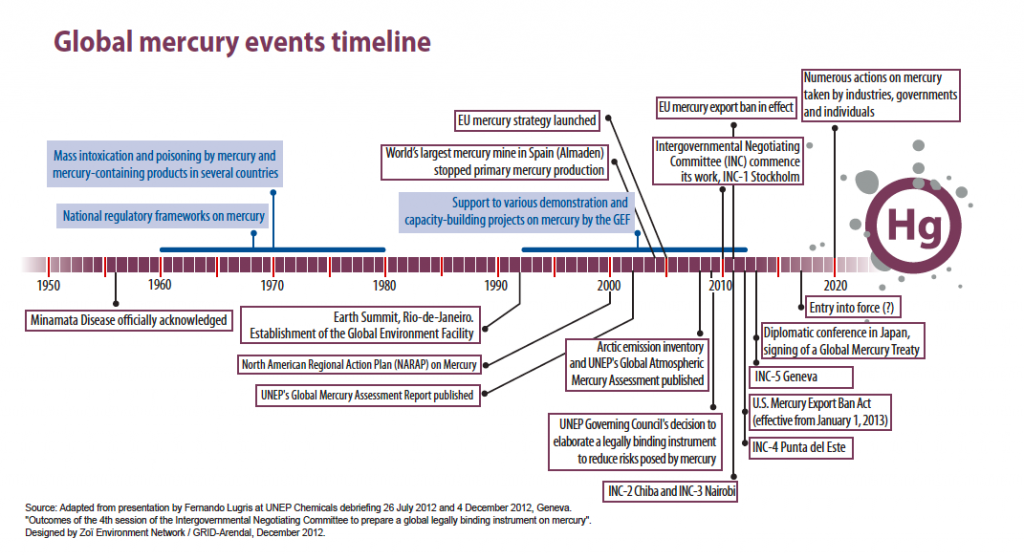

All mercury used in products and processes originates from deposits in the earth’s crust. Deposits are distributed around the world, with a large concentration in western Asia and China. Mines in Spain, Italy, and Slovenia were historically the main global sources of the metal, but most mercury mining today occurs in Kyrgyzstan and China.

Once extracted, mercury is traded as a global commodity. Annual international movements of mercury have historically been on the order of 1000–2000 tonnes per year. Nations that have existing mines aren’t the only exporters of mercury; a number of developed nations have existing stocks of mercury available for export, or they act as brokers between primary sources and importing nations.

On the issue of supply, the proposed treaty text bans new primary mercury mining and the export, sale, or distribution of existing mercury (except for the uses listed in Annex D II). While Annex D has been drafted, the specifics of the Annex are still being discussed, as is the question of whether any restrictions will be placed on existing mercury-mining operations.

The proposed treaty text also requires that parties identify all mercury stocks within their territory. However, the threshold size of these stocks is not yet stipulated. We expect that this will be a subject of debate during the remaining days of the negotiations.

In terms of trade, the proposed text mandates that mercury can only be exported for allowable uses, as described by the treaty, or for environmentally sound disposal. It also requires that exporting countries obtain written consent from the recipient country. This section of the text reflects the integration of the Basel Convention, which concerns the global transboundary movement of hazardous wastes, into the mercury treaty. Of particular importance, the proposed treaty text also invokes the principle of “prior informed consent” from the Rotterdam Convention. The specific responsibilities of exporting and importing countries, as well as the extent of guidance that the Conference of the Parties is expected to provide on this front, is and will likely continue to be the source of some interesting discussion among involved parties.

The mercury supply and trade issue is now being discussed in a focused “technical articles” contact group. We hope that delegates are able to make significant progress on this front in the hours ahead so that we can move onto addressing artisanal and small-scale mining, discussing waste and storage, and—ultimately—reaching agreement on an effective global mercury treaty.

Follow us on twitter @markdstaples and @DanyaRumore as we post live updates on the negotiations!