By: Julie van der Hoop

My experiences in Geneva at INC5 were those I had never expected. Though we had played Leah and Noelle’s ‘Mercury Game’ to prepare us for what negotiations might be like, there were so many things that this game didn’t prepare me for.

I never thought…

… I’d be so interested in financial assistance

When I was assigned to pay specific attention to articles pertaining to financial and technical assistance, I was a bit upset. I had my fingers crossed to be in the group on Institutions and Implementation, as I thought it would be most relevant to my research. But having read up on the financial issues for this and past treaties, before I knew it I was completely enthralled. I couldn’t wait for contact groups, or to listen to countries argue over the use of ‘provide’ vs. ‘promote’ vs. ‘facilitate.’

… Scientists’ roles were “just beginning”

In a quick exchange, a delegate mentioned that the role of scientists would begin once the politics ended. Post-treaty, he suggested, science is needed for research, monitoring and reporting. I suggested that the major role we played was before the politics had begun – science identified the issues, the mechanism, the transport, etc. This interaction, along with many other experiences, really made me think about how I felt science and scientists fit in to these policy issues.

… Delegates don’t have a 9 to 5

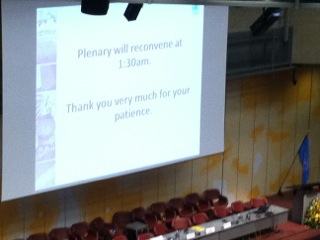

When Noelle had warned us that under pressure talks could run late into the night, I wasn’t sure how far off the business schedule we would stray. We learned, first hand, that delegates have more of a 9 to 5am, and that breaking for meals can be more of a privilege, not a right.

… I’d be able to stay up late

Most people who know me are aware of my early bedtime. I rise early, I sleep early, and I like to keep things consistent. Plenary was scheduled to end at 11pm daily, a time when I’d usually have already moved towards bed. So when it routinely went much later and was even postponed until 1:30 am, I am surprised that I made it through.

Whether it was the hilarity of the Swiss Breaks (cheese fires included), extended tango dancing metaphors, overuse of Queen’s Hot Space album, or our interest as graduate students to make the most bang for our buck in piling our buffet plates, I laughed a lot this trip. Yes, mercury is a serious issue and it needs to be treated as such. But taking the time to make snow angels at 2:00 am or write acrostic poems of country positions can help balance the mind, or at least keep one awake.

I had low expectations of sightseeing, but luckily we had a chance to catch a couple of sights on the last day (after having slept a couple of hours!)

… Get twitter.

#Seriously.