by Leah Stokes and Rebecca Saari

Each year, humans mobilize around 2000 tonnes of mercury, with about 90% emitted to the air and 10% released to land and water. Since releasing mercury leads to environmental and human health impacts, addressing emissions and releases needs to be a central part of the global mercury treaty.

The draft text of the treaty, developed during the INC4 in Uruguay, distinguishes between emissions to the atmosphere and releases to land and water. However, the extent of controls on anthropogenic emissions remains to be seen, and it is possible that releases will be excluded altogether.

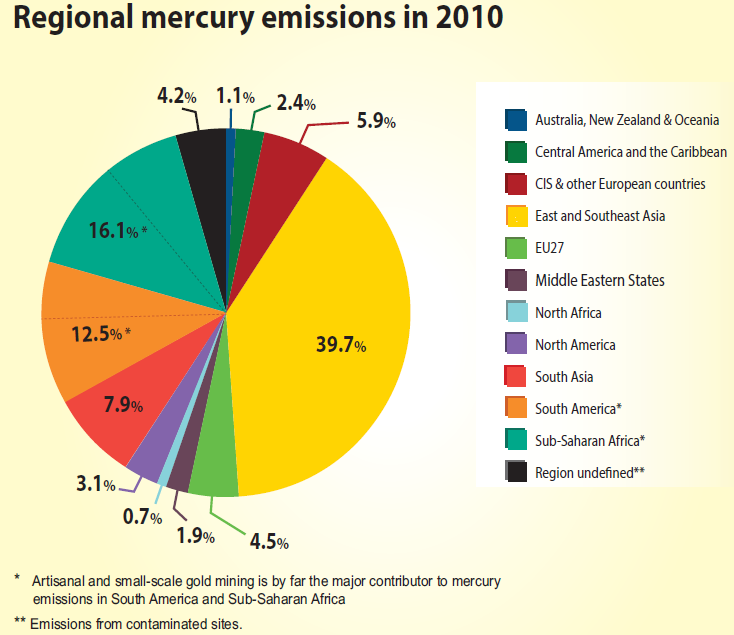

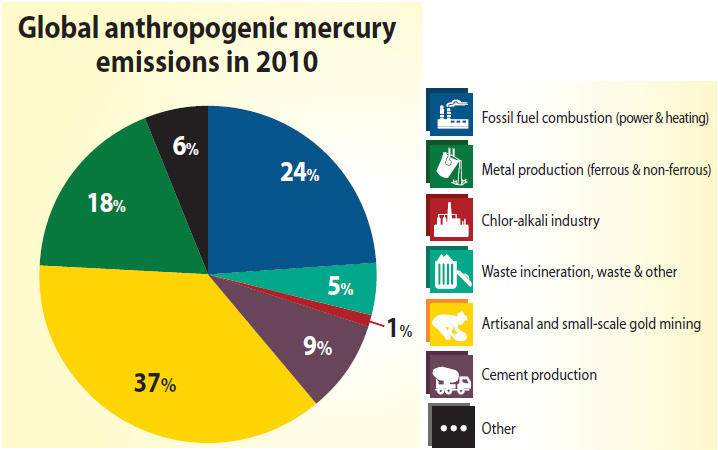

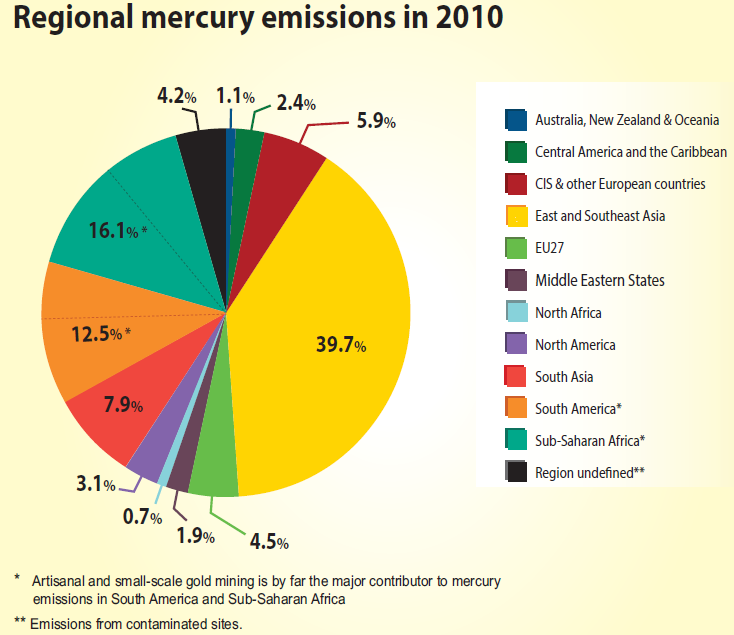

UNEP’s 2013 estimation of 2010 emissions from each global region. These estimations significantly changed since the 2008 reports, where East and Southeast Asia was estimated to contribute two-thirds of global emissions. These changes likely reflect a reduction in the estimation of mercury from coal power plants in Asia and an increase in the estimation of mercury from ASGM in Sub-Saharan Africa and South America.

Currently, almost 40% of mercury emissions come from East and Southeast Asia. Many developed countries have significant regulations on emissions, and the treaty is in part an effort to have all countries adopt standards. Yet most historic emissions came from the developed world. As is the case with climate change negotiations, this dynamic raises equity issues – mainly, who should pay: past emitters or current emitters?

Unlike carbon dioxide, however, mercury is toxic with acute health and environmental impacts, and its release is not tightly coupled with countries’ GDP. For this reason, all countries should be interested in reducing their mercury emissions and releases.

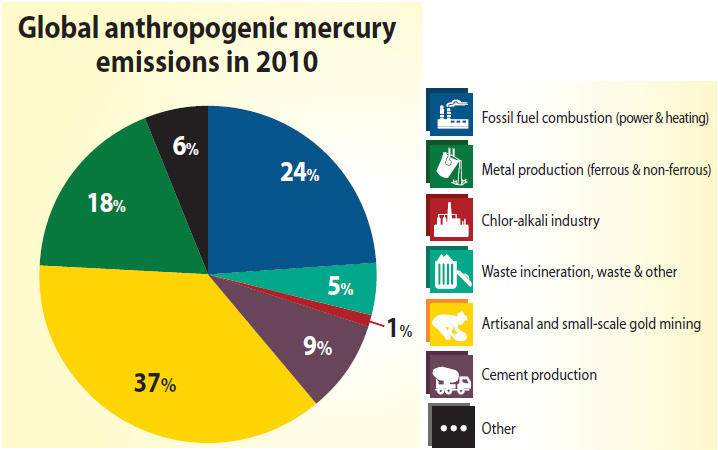

UNEP’s 2013 report, “Time to Act” recently updated the proportion of emissions from each source in 2010. ASGM is now the largest estimated source of emissions, with coal plants in second place.

About one-quarter of all global mercury emissions to air come from coal-fired combustion, including power plants and industrial boilers. This suggests an important aim for the treaty is reducing mercury emissions from coal-fired power and heating. There are many ways to achieve this, including pre-treatment of coal and various post-combustion technologies. These options also reduce co-emissions of other harmful air pollutants, and conventional post-combustion treatment can be enhanced to remove 80-90% of mercury emissions. Mercury-specific post-combustion control, which can achieve 90% mercury removal, is also available.

With a variety of emissions control options available, and significant variation in the mercury content of coal, the Chair and delegates are challenged to set appropriate goals and measures. When asked, most countries that currently regulate mercury responded that they employ emissions limits, or limits to the amount of mercury exiting a stack (flue gas concentrations).

Thus far, proposed flue gas limits range from 0.01 to 0.2 mg/m3. For reference, 0.05 mg/mg3 is one of the highest values measured at a series of US plants with limited pollution control through a fabric filter and a low-NOx boiler. In other words, a standard set as high as 0.2 mg/m3 could imply almost no control technology at all (See document: UNEP(DTIE)/Hg/INC.5/4 for more details). Ultimately, the level of control technology required will dramatically affect the treaty’s effectiveness.

While coal-related emissions present a clear priority, other mercury emissions are challenging to address, since they comes from a wide variety of sources, including: gold, cement and metal production, the chlor-alkali industry, waste incineration and dental amalgams. The Chair’s most recent updates also highlighted mining tailings, and sewage and wastewater treatment plants as potential sources. Over one-third of all emissions are from artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM), which is addressed in a separate part of the treaty. Decisions on ASGM will dramatically affect global emissions, given that the UNEP 2013 report recently named it the largest source of emissions.

This week, countries have many decisions to make on mercury emissions and releases. Which sources should be controlled—existing or new plants, and from which industries? For examples, it is currently unclear whether the oil and gas sector will be included as a source.

Should small sources be exempted from requirements to inventory and reduce their emissions, and if so, what would the threshold be for a “small” source? Potential thresholds for required controls are listed in the Chair’s documents. For example, coal-fired power plants smaller than 50 MW could be exempted from mercury control technology. For context, 20% of all US coal units are 50 MW or smaller, meaning that this threshold could exempt a significant proportion of plants.

What should the goal be – should the treaty set reduction goals, emission limits, or require best available techniques? As the discussion about flue gas concentrations implies, these standards will have significant consequences. And finally, how flexible should the requirements be—should countries have to commit to specific standards, or can they develop flexible national plans and report at a later date?

The draft text reflects many of these debates. Article 10, which addresses atmospheric emissions, has two options: one, which would require goals, best available techniques or emissions limits; the other, which would require national plans. These issues and many more will need to be decided in the coming week. Decisions on atmospheric emissions and releases to land and water are essential to shaping the treaty’s ultimate environmental and health impacts.