By: Leah Stokes

The second day of negotiations at INC5 was a busy day, without any Swiss breaks. Delegates spent significant time discussing key articles on Products & Processes, and Emissions & Releases. Here are some updates from our team’s observations on the proceedings so far.

Products & Processes

The technical working group focused on products and processes started early and has powered through the entire day. There was a lot of back and forth between the US, Canada, EU, Japan, and the African Group on the one hand and China, India and Brazil on the other about phase-out dates. China was particularly persistent that they could not phase out mercury batteries by 2020, because there are no mercury-free alternatives currently available to China. Compact flourescents and lamps were also hot topics; negotiators broke off into a smaller group around 11:15 PM to try to reach agreement on mercury concentrations and phase-out dates.

The working group has a new co-chair, Donald Hannah from New Zealand. He delivered an inspiring speech at the beginning of the session and set some ambitious goals. “Finding problems with text is unacceptable at this stage of the process,” he told the delegates. “We are not going to let perfection get in the way of a good text.” His expectations for a cooperative and productive group have spurred the discussions forward. By 11 PM, it looked like negotiations on this issue would continue until the middle of the night.

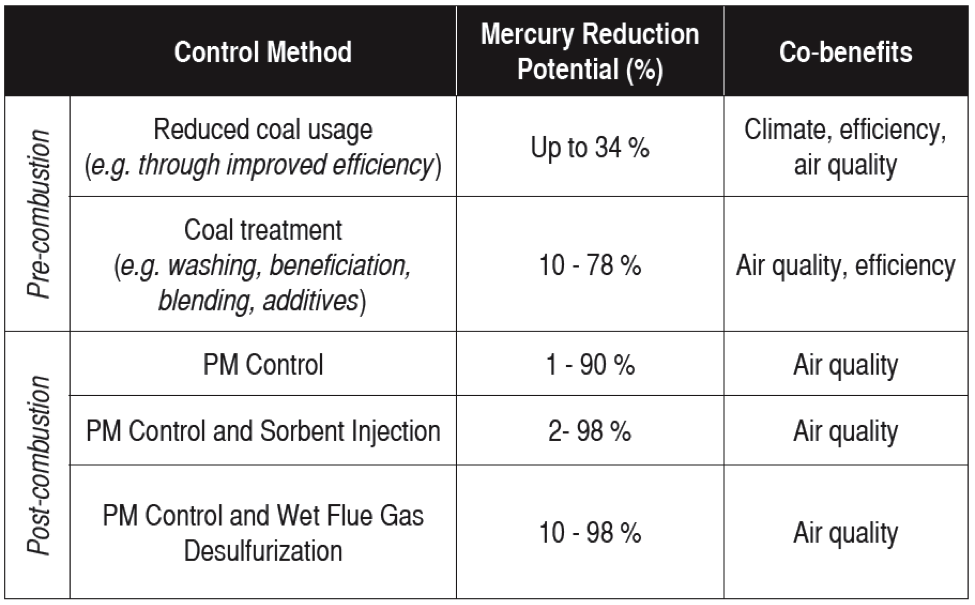

Emissions & Releases

This morning’s plenary session kicked off INC5’s discussion of mercury emissions to air and releases to land and water. Countries noted that emissions and releases were “crucial” and “at the heart” of the treaty. In the plenary, countries sorted into supporting a more stringent approach, binding targets and techniques–option 1–or a more flexible approach with national plans–option 2. With the notable exception of the African Group, developing countries generally favored a flexible approach, while developed countries favored a more stringent approach.

After discussing key issues, the Chair arranged a contact group chaired by John Roberts (UK) and a negotiator from Indonesia. Meeting in the afternoon, the group was tasked with resolving issues around: the use and nature of thresholds to exclude small sources; striking an agreement on the strength of the articles by specifying the precise requirements and controls; and deciding what distinctions should be made between emissions to air versus releases to land and water.

At the end of this meeting, the co-Chairs formed a team to craft the first draft of a new, compromise article (between option 1 and 2) that will specify precise requirements and controls while allowing sufficient flexibility. They are working busily as we craft this blog post. The results of their efforts will be discussed again in the contact group tomorrow. In addition, plans were made for a technical group to provide guidance on the options and implications for various threshold levels and sources in the coming days.

Institutions & Implementation:

Today’s discussions on institutions and implementation in the plenary focused on links with the Basel Convention. Negotiators emphasized there is a need to clarify linkages with Basel, which focuses on chemical waste broadly, and the section in the draft mercury treaty focused on waste. The Chair mentioned that many delegates here worked on drafting the Basel Convention, so he hoped that they would draw their attention to this task. The US notably brought attention to the fact that they had signed the Basel convention; although they have not ratified it.

Definitions was another key issue. There are some proposals for redefining use allowed to ease some of the disagreements in ASGM. More broadly, there is increasing concern that the draft treaty text be consistent across sections, to ensure a smooth implementation.

Financial & Technical Assistance

Discussion in the Financial & Technical Assistance contact group began with restating country positions and then moved to defining technology transfer. It is still undetermined whether the treaty will include both “soft” technology transfer – including best practices and know-how – and/or “hard” technology transfer – namely, the actual technology. As a result, delegates have yet to negotiate a streamlined version of Article 16bis regarding technology transfer.

Discussion of Article 16, regarding technical assistance, centered around whether technological assistance will only flow from developed to developing countries, or will be exchanged among all parties. This discussion was facilitated by a colorful and popular metaphor of countries ‘dancing the tango and deciding who will lead’—doubltless, some stepping on partners’ toes will occur. As of 10 PM, it appeared that all parties would cooperate to provide [something], to developing countries in particular. What that ‘something’ is remains unknown. Although the chairwoman from Jamaica is providing firm and insightful guidance, there is still much to be decided in this area.

Supply & Trade, ASGM and Waste

Supply & Trade, ASGM and Waste were all introduced in the afternoon plenary session today.

On Supply & Trade, countries debated whether to ban existing and future primary mercury mining, with Chile arguing a ban would set a precedent for other treaties. In addition, the specificity of import/export procedures and their similarity to the Stockholm and Rotterdam conventions was a critical issue, as was the question of whether Prior Informed Consent was needed before mercury was traded.

On AGSM, parties discussed whether text should be included for the phase-out of mercury use in ASGM and whether paragraph 6, concerning financial and technical assistance, should be included or deleted. It was unclear whether banning mercury use in ASGM would just push demand for mercury into a black market.

Finally, on waste, the definition of “mercury waste”, and the use of “shall” rather than “may” were discussed in plenary.

The “technical matters” contact group was subsequently tasked with developing clearer text on all these issues. It is unlikely that the contact group will address these issues until late tomorrow.