The Mercury Negotiation at the United Nations in Geneva existed in its own time zone. At first I thought it was jet lag, but the Centre Internationale de Conferences Geneve (CICG), which housed the convention, must be in its own time zone; there are few other explanations.

Never before had I seen a meeting be scheduled to start at 1:30am. It started at 2:30, as if the delegates had tacitly agreed upon a daylight-savings-like clock change. I thought my watch must be wrong.

But, my watch is Swiss made. I bought it 17 years ago in Lucerne, Switzerland. I’ve only had to change the battery once. It is a simple, reliable time keeping device, or so I thought. My Swiss watch does not work at the mercury negotiations at the UN’s headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. The irony.

I didn’t immediately come to this conclusion, however. The problems with my watch developed slowly. I didn’t notice anything wrong with it during the first Plenary session on the first day. Perhaps that was because I was fascinated by the simultaneous interpretation into 6 languages and by testing my French and Spanish, before returning to my native English (channel 1 on the headsets). Or, maybe my attention was occupied in trying to match the delegates faces with their voices, or even harder – to their tone as conveyed by an interpreter’s voice.

The first Plenary was exciting to me because it was my first Plenary at an international negotiation. However, I quickly picked up on the pattern. Every delegate commenced his/her remarks with compliments to the Swiss’ hospitality, intentions to work with the other delegates to reach an agreement, and niceties to Chair Fernando Lugris. It was only towards the end of their moment on the floor that they spoke their country’s position. My watch worked fine.

The first Plenary was exciting to me because it was my first Plenary at an international negotiation. However, I quickly picked up on the pattern. Every delegate commenced his/her remarks with compliments to the Swiss’ hospitality, intentions to work with the other delegates to reach an agreement, and niceties to Chair Fernando Lugris. It was only towards the end of their moment on the floor that they spoke their country’s position. My watch worked fine.

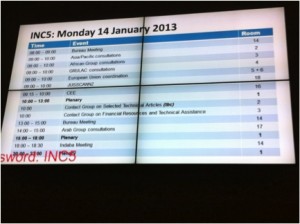

It was during the first evening’s session of the contact group on selected technical articles that I started noticing the first signs of trouble with my watch. They worked until 11pm. I don’t mean they worked late, grad student style: lounging in chairs in comfy clothes, a laptop apiece. They remained in business attire in a facilitated meeting, with the co-chair allocating speaking time. I couldn’t believe they were still so formal so late at night.

The next morning, I thought my watch was outright lying. It couldn’t be time to get up already. My teammate, Bethanie and I hustled through breakfast to get to the CICG for the contact group’s morning session only to find the break out room empty.

From there my watch just got worse. One night, though I can’t remember which one because my calendar stopped working too as the days all blended together with only a few hours sleep in between, the contact group co-chair announced a five minute break. Forty-five minutes later, by my watch, the delegates weren’t back in the conference room. Does one CICG minute equal 9 minutes on my watch?

But a pattern was emerging. The, now nightly, “five-minute breaks” coincided with the closing of the conference center’s café. Furthermore, the contact group adjourned reliably close to the start of each of the Swiss Breaks, with their wonderful offerings of cultural food and drinks. And, my body clock was operating in a time zone somewhere over the Atlantic.

When the contact group reconvened after a coffee break or a Swiss break, the text in Articles and Annexes was different or the group would easily agree to text that had been contentious before the break. What was happening during these breaks?

Unfortunately, as observers, we weren’t privy to these informal discussions. However, the co-chairs referred to meetings with delegates and talking ideas around. Pairing this with the small working groups they’d send out to address particular technical issues like the threshold of mercury allowable in different kinds of lightbulbs, and my watch’s time warp became productive.

It’s not that time was nonexistent in the CICG. Chair Lugris and the co-chairs of the contact group on selected technical articles frequently reminded the delegates of the ticking clock. The message in the Plenary was humorous and musical as Chair Lugris took to ending each plenary session with Queen’s “Under Pressure.”

These reminders became more effective as the final day approached. Delegates started including some variation of the comments, “in the interest of flexibility” or “to keep things moving along” in their remarks.

Somewhere out in the edges of the INC5 time warp an agreement was forming. Was the shared sleeplessness and Swiss cheese and chocolate creating a cohesion among these delegates from roughly 140 countries? Was the emerging agreement something they can bring back to a supportive reception in their home countries? In some of the delegates’ remarks, this two-level game was very evident. Delegates were constantly balancing their commitments to their home country’s interests with the pressure to reach agreement at INC5.

The text was formally adopted at around 7am on the final day of the INC5 convention, which was not the early start it sounds, but rather a late finish. Sleep-deprived but excited delegates expressed their congratulations and gratitude to each other and their hope for the treaty. As the blur of INC5 receded into the new reality of text to be brought to home countries, the treaty signed, and then ratified, the sense of accomplishment was palpable. Although not everyone was happy with the result, most particularly the representatives of the Minamata Victims felt the treaty was not strong enough as the IPEN NGO expressed through a poignant speech.

Somewhere during the adopting of each article and annex in turn, my watch started working again. During the celebratory party my watch clearly told me that 8am is too early for cake and Champagne and that I needed sleep.

By the time I stood at the Geneva train station the next morning, my watch said the same time as the beautiful Mondaine station clock, and exactly coincided with the trains’ arrival. I had left the INC5 time zone.