By: Bethanie Edwards

What do compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFLs), dental fillings, PVC, and paper mills have in common? The intentional use of mercury, of course! While toxic, mercury does have remarkable chemical properties that humans have exploited since antiquity. But, mercury added products and manufacturing processes increase release of mercury into the environment. Luckily there are a number of alternatives, restrictions, and control mechanisms that can be put in place to decrease mercury emissions from this sector.

While the mercury in each CFL has declined from 50mg to 2mg in the last three decades, 13% of the mercury contained in CFLs still makes its way into the environment over a product’s lifetime. Recycling bulbs properly and using protective packaging in transit can reduce releases into the environment. However, consumers should consider how their electricity source may influence net mercury emissions. If you live in an area powered by a coal, using CFL bulbs can decrease your carbon footprint and reduce the mercury being emitted into the atmosphere by reducing the amount of coal burned (remember, coal burning is one of the largest sources of mercury). But if you live in an area powered by hydroelectric energy, replacing all your traditional incandescent bulbs with CFLs will reduce your energy consumption but actually increase your mercury emissions.

Dental amalgams or “silver fillings” bind together mercury and other metals and cap the tooth, preventing further decay. Porcelain and compost fillings are alternatives. However, “silver fillings” are cheaper, more durable, require less skill to apply, and represent an important option as access to dental care increases in low-income countries. To reduce the amount of mercury emitted to the environment from the dental amalgam industry, porcelain fillings could be used when affordable or control technologies such as amalgam traps that prevent the mercury from entering the waste stream could be used when “silver fillings” are unavoidable. There is active discussion at INC5 on what to do about dental amalgams.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is a widely used construction material. The original method for making PVC required mercury to catalyze the reaction. While a slightly less efficient mercury-free pathway has been utilized by most nations since the 1950s, China and Russia have yet to phase-out the mercury catalyzed method.

Chlor-alkali production also releases mercury. Paper production is the leading demand for caustic soda, a chlor-alkali output, which is used to bleach paper pulp. There are two alternative pathways for chlor-alkali production that do not use mercury. China is the major consumer of mercury in the chlor-alkali industry, whereas, over the past 15 years chlor-alkali plants in other countries have been successfully converted to membrane-based technology, which does not use mercury.

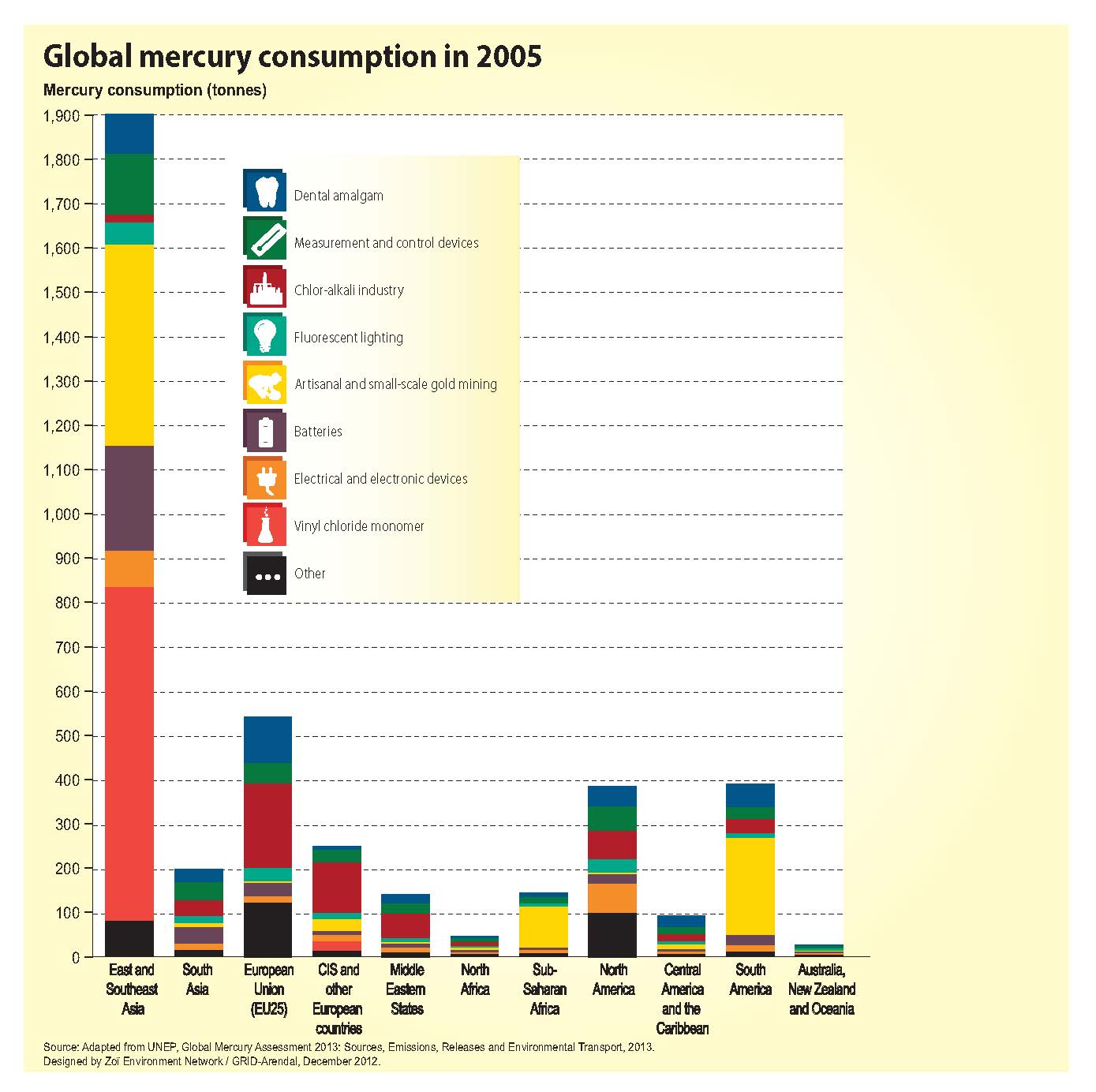

There are several other products and processes that utilize mercury such as, batteries, cosmetics, measuring devices (thermometers and blood-pressure meters), and electronic switches. Batteries have been successfully phase-out through national level initiatives in most countries. However, China still manufactures some mercury batteries as well as thermometers and blood-pressure meters. The US and other nations have also taken domestic action to phase out mercury in electronics. The graph below provides a breakdown of mercury consumed by geographical region according to each product and process.

Mercury used in products and processes in 2005 for each region. From the UNEP 2013 Mercury Assessment.

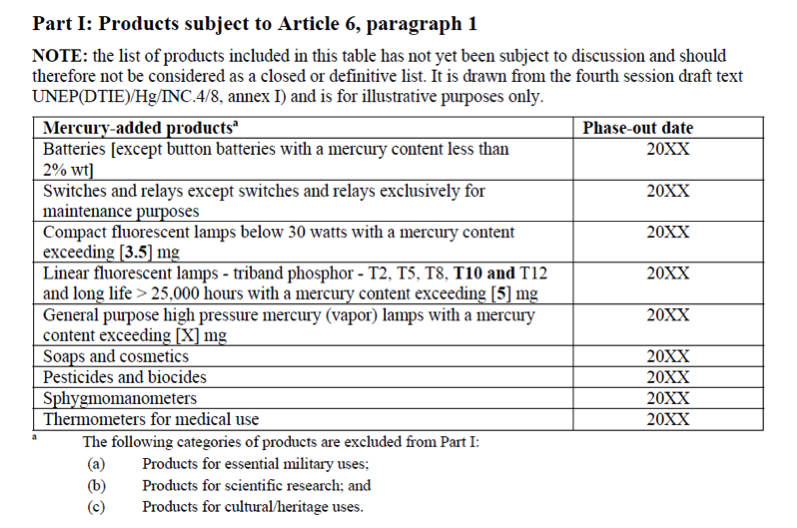

During the last negotiating session there was an on-going debate as to whether to use a positive or negative list to restrict mercury products and processes. A negative list approach entails a general ban on all mercury added products and processes with a list of exemptions. For example, if a negative list was adopted, all processes that utilized mercury would be prohibited. China could petition the UN to allow the continued manufacturing of VCM using the mercury until they could convert all plants to the alternative manufacturing method. A positive list would only restrict specified products and processes. So if VCM production was not listed as a banned or restricted process, China could continue manufacturing VCM.

Clearly, the negative list is a more aggressive way to reduce the consumption of mercury as only successfully petitioned products and processes would be allowed. However, for many countries the positive list is much more favorable as it ensures economic flexibility. China, the US, and Canada were strong supporters of the positive list. The African Group was a strong proponent of a negative list, reflecting the concern that mercury added products would continue to make their way into Africa as waste. The positive list vs. negative list debate calls into question whether targeting the product and processes that are the largest emitters is adequate or if all mercury products and processes must be addressed.

Right now the draft text lists a number of mercury-added products as to be phased-out by an uncertain date, although the list of products is subject to change as the delegates negotiate. Dental amalgams are subject to restriction. For processes, mercury use in chlor-alkali production is currently on the phase-out list with a date of either 2020 or 2025. VCM production is currently subject to restriction but is not banned. This is noteworthy, since in 2010 VCM production in China (East and Southeast Asia) alone led to more mercury consumption than all products and process in every other region. In short, this is a very important issue.

How the international community arrives at an agreement on limiting products and processes is sure to be a lively and crucial debate. Be sure to keep an eye out for a follow up report on how it all pans outs.