By: Amanda Giang and Philip Wolfe

Many moons ago, before the negotiations began, we set up some key questions about how a treaty actually works in this post. We called these questions the implementation problem: how does a treaty actually get implemented? How do we make sure that countries are actually following its provisions? How do we make sure the provisions are effective? And what does all this mean for the relationship between countries, between treaties, and between different international bodies?

Now that the negotiation is over, we can try to answer these questions for the newly minted Minimata Convention.

1. How will the convention be implemented in practice?

While the Minimata Convention was adopted last Saturday, it won’t be officially open for signature until October, in Kumamato, Japan. Once a country has signed the convention, they will have to begin the domestic ratification process, which involves putting in place legislation that implements the treaty’s provisions.* When fifty countries have ratified the treaty, it enters into force, which means that it becomes binding by international law.While countries prepare for implementation, they will have option of preparing National Implementation Plans (NIPs). This flexible approach to implementation plans was a compromise between mostly developed countries, who pointed out that NIPs are expensive and burdensome, and mostly developing countries, who were seeking financial and technical support to better understand how to implement the treaty requirements.

* If a country does not sign the convention within a one-year period, but then would like to join, it accedes to the treaty.

2 + 3. How can the convention ensure compliance and effectiveness?

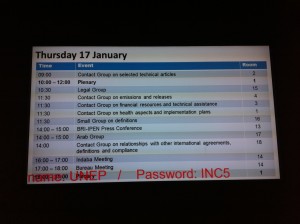

During the negotiation, one delegate said, “Reporting is the backbone of compliance,” referring to the importance of transparency and information exchange as a crucial incentive for following through on promises. Provisions for reporting and information sharing did not change drastically between the draft text and the finalized treaty. Reporting related to specific articles, such as supply and trade, products and processes, emissions and releases, waste and storage, and ASGM, are mandatory. Countries are also asked to “facilitate” other information sharing activities, like diffusing economically and technically feasible mercury-free alternatives to products and processes.

As many delegates noted, even if parties are complying to the treaty’s requirements, there is no guarantee that these requirements will translate into the desired objective of the treaty—to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury. If everyone is in compliance, but the objective is not met, the requirements of the treaty may need to be changed. Monitoring and modelling concentrations of mercury in the environment, in biota, and in particularly vulnerable or at-risk human populations is therefore a cornerstone of evaluating effectiveness. The treaty encourages parties to cooperate on these monitoring and modelling activities, but does not mandate it. A serious remaining question then, that may be addressed in the first Conference of Parties, is whether and how much funding will be provided for these activities.

4. How will this treaty interface with other international agreements and bodies?

The final treaty text deals with relationships to other international agreements and bodies in the preamble. The preamble recognizes that the Minimata Convention does not create a hierarchy between other international agreements, and that treaties and international bodies concerned with environment and health are mutually supportive—particularly the World Health Organization, and the Basel and Rotterdam Conventions. The preamble also makes special mention of the Rio+20 reaffirmation of the Rio Principles, with special emphasis on common but differentiated responsibilities.

During the negotiations, there was a heated debate over whether or not there should be a dedicated article for health aspects. Many countries felt that including such a section—which would focus on identifying, monitoring, providing information to, and treating adversely affected and vulnerable communities—would be out of scope and redundant given the mandate and expertise of the World Health Organization and International Labour Organization. In the end, this article was included in the text to reflect one of the key objectives of the treaty—to protect human health. However, this article recognizes the role of the WHO and ILO and calls for increased cooperation with these bodies. The article also does not require that parties undertake these health-promoting activities for affected and vulnerable populations, or set aside funding for these activities. Instead it asks that parties promote these activities.

5. How will this convention appropriately address individual parties’ conceptions of sovereignty?

These international negotiations can be thought of as a two-level game: each country is simultaneously thinking of the global sphere and its own domestic position. As such, countries are willing to sign on to the treaty if it is somehow in both its self-interest and the interest of the international community. When it came to defining a “mercury compound” in the treaty, a tension developed as countries reached for a definition that would be relevant to curbing deleterious mercury emissions and releases, but would still be broad enough as to not constrict domestic regulators. For instance, if naturally occurring trace amounts of mercury containing compounds occur in the soil of a given country, would the country be required to regulate its own topsoil? If some countries have difficulty ratifying treaties that require prior informed consent of trade, should this treaty not include prior informed consent requirements just so those countries can be party to it even if it leads to a weaker overall treaty? If this convention is able to phase-out all primary mining of mercury, will it set a precedent that could lead to the phase-out of other forms of mining in the future?

While we’ve seen some of these debates resolved, the true test of this question will come as individual parties move to sign and ratify the treaty.

by Amanda Giang

by Amanda Giang