by: Rebecca Saari

Sitting in my desk in Cambridge, MA, folks around me ask, “How was Geneva?” Even through the fog of jetlag, it’s clear it was an amazing, unique experience. If I had to sum it up, it was so very:

So Swiss

Both in and out of the convention center, we enjoyed the alpenhorn, yodeling, Heidi, chocolate, bakeries, fashion, fondue, history, and everything in miniature.

So Cosmopolitan

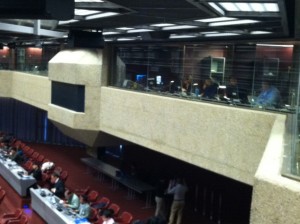

On the first day, before plenary began, I remember scoping out the placards of the 140 countries in attendance. I even got to meet some of the faces behind those placards, sharing a joke with folks from Qatar, Russia, Switzerland, and the US, finding fellow  Canadians, and enjoying the hospitality of the other NGOs. It was humbling practicing my French, especially around the UN interpreters, with their impressive skill, energy, and personal flair.

Canadians, and enjoying the hospitality of the other NGOs. It was humbling practicing my French, especially around the UN interpreters, with their impressive skill, energy, and personal flair.

So Intellectual

I really enjoyed hopping through museums and historical buildings in Switzerland, hearing how to make the most of my time here in Cambridge, and getting reintroduced to poetry and literature by a group of MIT scientists and engineers.

So Romantic

If you can develop a “meeting crush”, then I fell hard in Geneva. I watched with admiration, as, in multiple languages and throughout all hours of the day, the chairs and co-chairs helmed a conversation that was variously plodding, meandering, or maddening with unerring grace, clarity, wit, and authority. Plus, Chair Fernando Lugris can tango.

http://www.iisd.ca/mercury/inc5/17jan.html. Co-chair talks to delegates from India.

http://www.iisd.ca/mercury/inc4/29jun.html Fernando does the tango.

So Popular

Being involved in public outreach was a first. This is definitely the first time I’ve ended up in candid photos taken by journalists… in the snow, with a goat, you name it.

It was fun connecting with other folks interested in mercury, and watching our blog garner some interest. Some posts were more popular than others. Pop culture, health, animals, cool trivia? Yes. My overly technical opuses? Less so. It was a good lesson in communicating complex topics. I hope I’ve learned it; if my number of twitter followers stays in the low double digits permanently, that would be sad.

So Scientific

Science came up in surprising ways during the talks, whether it pertained to chemical compounds, units of measurement, control technology, or emissions estimation. It was interesting to hear the engineers and lawyers trade interpretations of the text – these are definitely distinct skills.

So Educational

Before we arrived in Geneva, we took a course on global environmental science and policy offered by the MIT Engineering Systems Division. In it, we played a few negotiation simulations. Our experience with the games made it exciting to watch the real delegates break into informal groups; it seemed like we were watching the real work of the meeting, and it was just like when we played the simulations in class. If you want to see what I mean, the mercury game is available online.

That’s all from me! Thanks for reading.

by Amanda Giang

by Amanda Giang