By: Leah Stokes

The negotiations ended a little less than a month ago. Life is back to normal. No more early morning wake ups and late night sessions with delegates from around the globe. The treaty text is finalized, with just the diplomatic convention pending. When I reflect on the final round of negotiations in Geneva, a few thoughts have come to mind.

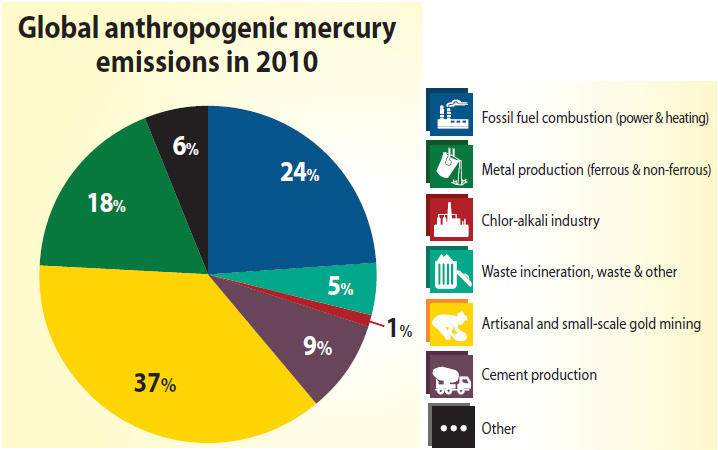

1) How little the media covered the negotiations. Compared to any round of the climate talks, the mercury treaty largely went ignored. This despite the 15 million people who rely on mercury for small-scale mining, and the 100 million people in turn who rely on these miners. Mining gold with mercury contributes 25% of total global gold production. And using mercury for this purpose is probably the biggest source of acute exposure. To me, this is a compelling story for any news organization. We’re talking about the fate of a group of people that amounts to several large cities. Yet, the world stayed largely silent. The lack of media coverage, in my opinion, probably helped to water down the strength of the agreement.

2) How much the text’s ambition declined over time. At the beginning of the week, there was the possibility that the treaty would meaningfully address emissions, whether from coal plants or ASGM. But by week’s end, the text was allowing countries to take five years just to inventory their emissions, let alone begin to control them. I understand that building an inventory takes considerable time; but we need to view this agreement from a longer time frame. These countries started talks in the early 2000s. Countries have already had a decade to get a handle on their emissions. It’s time to start decreasing emissions now. Unfortunately, this agenda item got dropped along with thresholds, ambitious timetables for reductions and clear targets. These issues, instead, were punted to the first round of the Conference of the Parties (COP) after the treaty is official signed this fall.

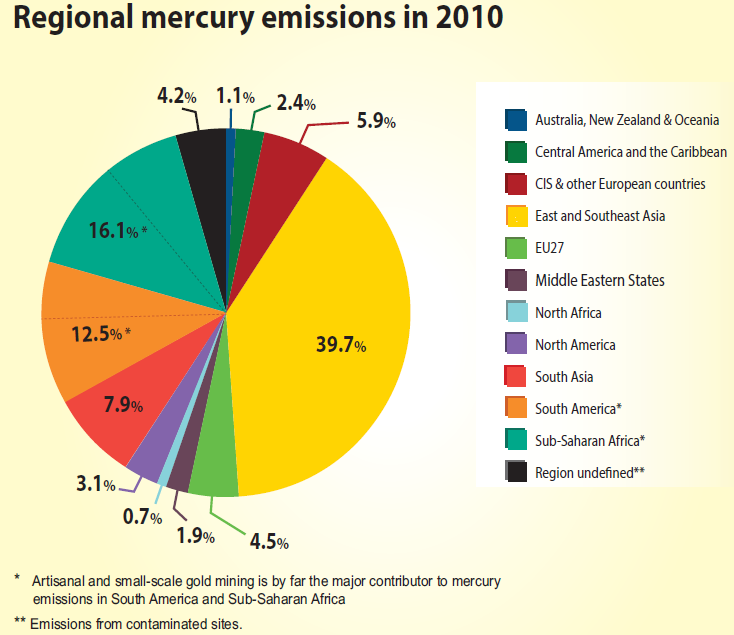

3) How much the treaty is a process, not a destination. It was tempting to view these negotiations as the final period on a run-on sentence that needed to end. Instead, they were just a mid-point in a long term project to reduce emissions. Getting countries to focus on the mercury problem is like peering through a prism to see the way the particular angle focuses the problem. I was surprised, for example, when ASGM emissions were deemed larger than coal emissions at UNEP’s scientific briefing at the beginning of the week. In my mind, this changed the priorities for countries, and made mercury emissions even harder to reduce. Future meetings will no doubt update the picture we have on the nature of the mercury problem and how well countries are addressing it. While finalizing a treaty is a noteworthy moment, international environmental negotiations are truly a multi-year decision-making process, with scientific uncertainty and shifting goals. It’s not over yet. And it’s possible the Minamata Convention will grow sea legs over time, allowing countries to steadily reduce mercury emissions on a more ambitious timeline once the treaty is implemented.