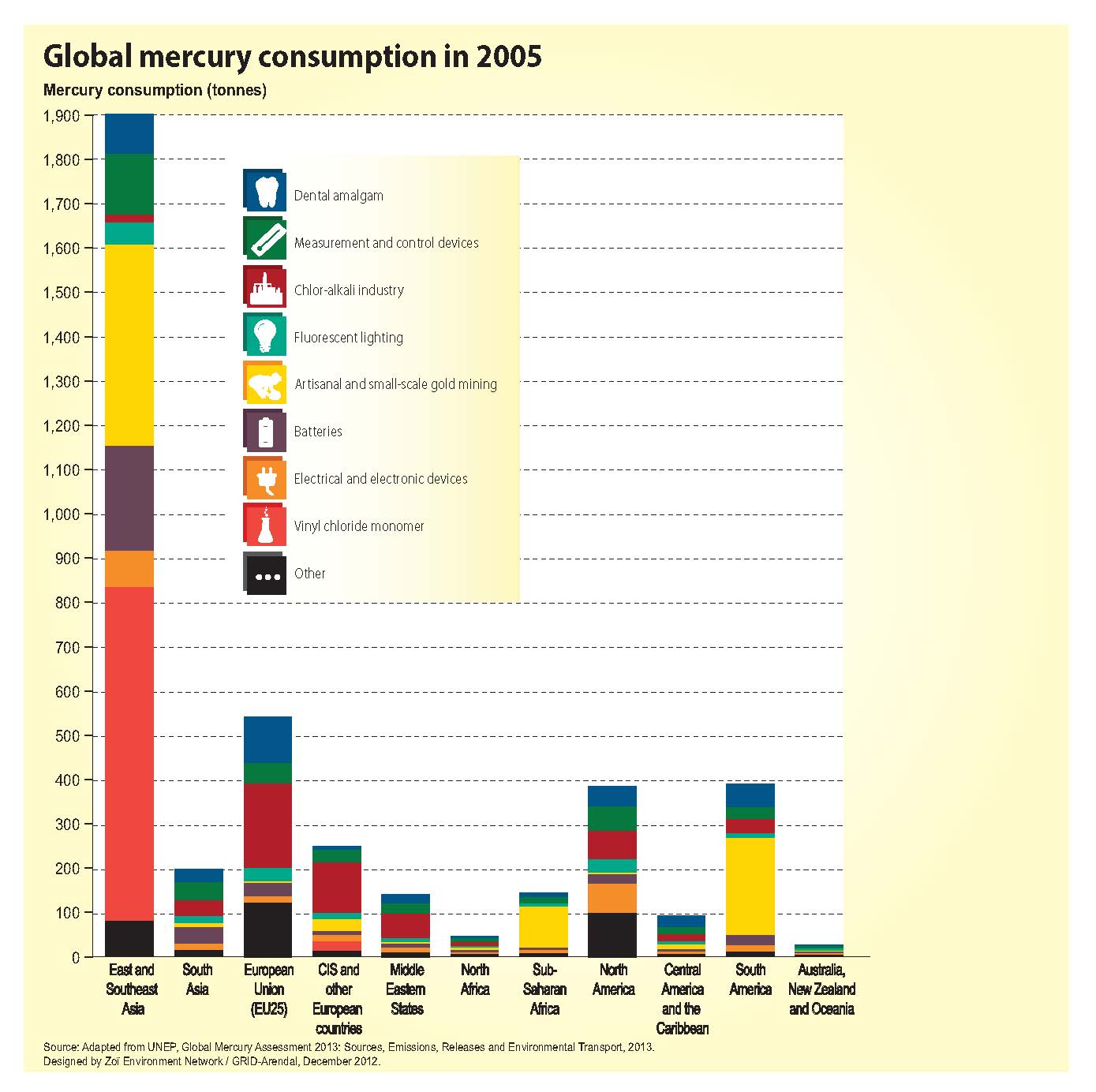

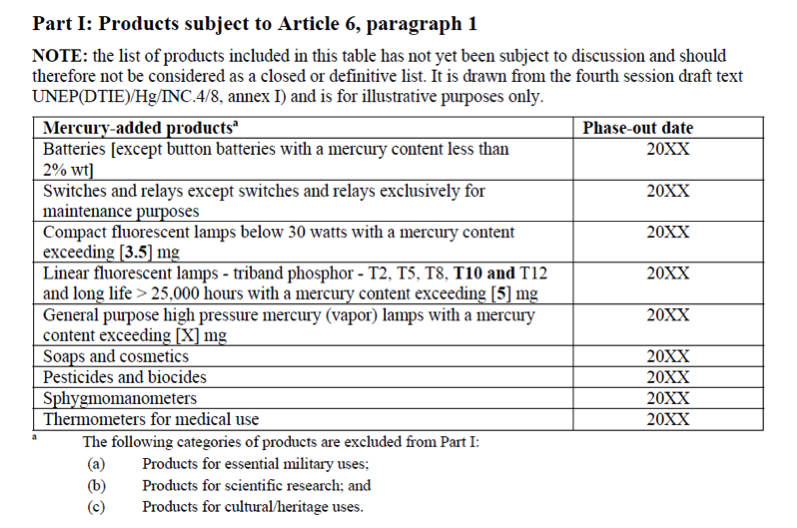

I will happily admit that going into the INC5 I probably knew the least out of our group about international negotiation. I study the chemistry of bacteria in the ‘twilight zone’ of the ocean. Consequently, my research does not directly intersect with policy often. So, I really did not know what to expect. I chose to cover mercury added products and manufacturing processes. I figured that my chemistry background and familiarity with synthesis processes would make this issue more accessible to me than say, covering financial assistance and capacity building. Before the trip I inhaled UN assessments, technical reports, and a few journal articles on the life cycles of mercury added products like compact fluorescent light bulbs. As my fellow MIT students discussed salience and legitimacy, words that I am still grasping the full meaning of, I mentally prepared myself to wander outside of my laboratory comfort zone and into the territory of global policy.

To my surprise the INC5 was not that intimidating after all. I probably helped that I had a bright, insightful posse of MIT students surrounding me. But it was amazingly easy to become enthralled watching delegates try to strike a balance between economic feasibility and environmental stewardship, trying to decipher the hidden agendas of each nation, and speculating as to whether a treaty with teeth would be the outcome of the negotiations. Below are a few of my observations

1) Negotiations are a marathon, not a race. Even though all the really exciting stuff happened at the end of the week as the adoption of the text drew near, I caught the negotiation bug on Monday. I couldn’t pull myself away from contact group sessions that went until 1 AM even though the discussion was moving at a glacial pace. I was afraid I’d miss something important or a brilliantly funny analogy. I also couldn’t bear the thought of being late to Plenary in the morning, where we’d find out all the action that had occurred in other contact groups. So sleep became a rarity and by the end of the week I was exhausted. I’m not sure that it was totally worth it as I was so drained after the adoption of the text that I couldn’t even enjoy the champagne. But I did gain a better understanding of the physical toll negotiations take on the delegates.

2) As I was often observing negotiations until the wee hours of the morning, I found out that Geneva is a beautiful city at night. I’m sure she is just as wondrous in the day time but Lake Geneva at night and the way that the evening is ten times brighter with snow on the ground is enchanting.

3) I have a sneaky suspicion that debating whether to use the word ‘should’ or ‘shall’ in this or that paragraph is a stalling technique. In every contact group there were a few hour-or-more debates over word choice. In my imagination, a delegate in the financial assistance contact group is texting a delegates in emissions contact group, “Use the shall/should tactic NOW! Stall agreement on thresholds. I’m on the verge of securing $ for tech assistance.”

4) The young guns were well represented in the delegations. Many key negotiators were under 40 which was inspiring to see. The people in the technical articles contact group became very familiar with my favorite young negotiator, Diogo Coelho from Brazil. Watching him time and time again stand up and represent the interests of Brazil (as well as other developing nations) as the more seasoned negotiators dominated the floor, one would never have guess that it was his first negotiation except perhaps because he doesn’t look a day over 25.

5) The asynchronous nature of science’s ability to influence policy became very apparent to me. Good science does take time. But we can’t wait until the science is conclusive to start making policy; it would be too late. As a consequence, the policy decisions that we end up making may not be effective considering the actual nature of the problem. The 2013 Global Mercury Assessment was released while we were at the conference. New data shows that ASGM is a much larger contributor to emissions than previously thought, larger than coal. Imagine if that data had been in the 2009 assessment. How different would the adopted text be? Perhaps ASGM would have been the focus instead of emissions. How do we make international policy more adaptive to new scientific findings?

I’m extremely grateful for the opportunity to witness the negotiation and adoption of an environmental treaty firsthand. UNEP is no longer this black box to me that you stick science into and somehow magically you get global policy out. I feel as though I have a clearer understanding of how the negotiation process works, the crucial role science plays, and the difficulty of getting an effective treaty. I also learned so much from my MIT cohort about policy, literature, Twitter, sad BBC mini-series, and Canadian politics. I walk away from this experience with renewed interest in the intersection of science and policy, the influence of blogs, and the role of my generation.